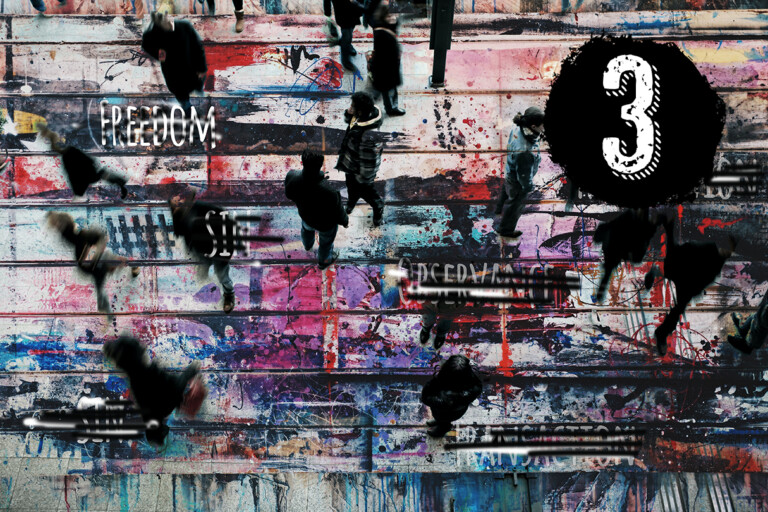

3) Thinking Deeply about Living Well

“A short word with an I in the middle” was how I once heard sin described. Living for myself and ignoring God. Then, according to the classic drugs-drink-and-debauchery testimony, life collapses, sinner repents, God cleans up the mess and everything is different. Great story. But it is rarely that simple, and most of the stories I can still recall suggest to me that the ‘I’ remained at the centre.

Yet again, we are describing a transactional event that is often called a ‘conversion’. Which is completely alien to anything Jesus taught, and has a very limited chance of making a lasting difference according to modern psychology.

So what do I mean by ‘transactional’? In simple terms it means that if I do something for someone, I expect something in return. The typical conversion story is transactional because it begins by defining God as a perpetual giver and me as the receiver of forgiveness and guaranteed salvation. Jesus has paid a price so that I don’t have to. If I were to strip the story above of all religious tropes and present it to a psychologist, she would be most likely to define the receiver as displaying traits of narcissistic behaviour. The giver has been trapped in an eternally abusive relationship.

Maybe that is why Jesus didn’t talk a great deal about sin. His intention was not to initiate a transaction, but an invitation. “The rule of God has arrived, come and be part of it”. But those who had the system sown up in their favour were offended. Their standard was law keeping. And they defined what the boundaries were. If the law was kept, they believed God would protect his people. Can you spot the transactional thinking? Jesus doesn’t look for sin at all – in fact he doesn’t seem to care when a sinful woman crashes a formal meal and washes his feet with her tears! Jesus is shifting the focus away from the Temple, which he says is going to be destroyed anyway, to relationships of reconciliation and adventure.

A number of years ago I began what has become an ongoing study into First Century Middle Eastern culture as a way of trying to understand Jesus’ teaching in its immediate context. I discovered that, to the Hebrew mind, sin is a far more dynamic concept than anything I had encountered in my Christian bubble.

The study truly messed with all my categories. The first thing I had to accept was that a Western preoccupation with being personally spiritual is not a Hebrew concept. Nothing can be truly personal unless it public. Sin, therefore, is not just thinking and doing things that sully me and harm others but a deliberate and persistent choice to be rather than to become. Or, to put it another way, sin is a refusal to change. Embarking on a journey of change begins with a willingness to leave certain things behind in order to journey to new destinations. But sin refuses to move on.

Sin certainly has “I” in the middle, and at the beginning and end. The things I do that others may call ‘sin’ are not the root of the issue. They are the symptoms. Just like the dwarfs in C. S. Lewis’ The Last Battle, who are surrounded by endless possibilities but are stuck in their tiny, dark world:

“Well, at any rate there’s no Humbug here. We haven’t let anyone take us in. The Dwarfs are for the Dwarfs.”… “You see, “ said Aslan. “They will not let us help them. They have chosen cunning instead of belief. Their prison is only in their own minds, yet they are in that prison; and so afraid of being taken in that they cannot be taken out.”

All this means that sin, if that word (with its historical and cultural baggage) is still helpful at all, is a refusal to change. A stubborn resistance to every invitation to change and growth, even when it is in our own best interests. The option to stay the same is considered attractive because it claims to put self first, but it fails in that goal. I have just one life and my determination to continue to be rather than to become closes down every adventurous and faith-filled use of that life. Our habitual nature, it seems, prefers a quiet, often solitary, life with its own familiar baggage intact, whilst the call of God is to shed hindrances and ‘follow’ him.