Blog Extra: How a Monk, a Psychiatrist, a Mathematician and a Rabbi help me live with constant pain.

This topic is something we are likely to return to. Like most people, we (the NC associates) have experienced significant illness, and like some people, we have experienced life-affecting disability. Simon was recently asked to write a blog post for The Grace and Truth blog, but he wrote far too much! Jon, who curates the G&T blog, kindly tamed the beast for wider consumption. You can find Simon’s original article below, and the edited version here.

1996 was a tough year. I had been a Christian for 13 years and the tap of the Holy Spirit had been turned off. 1995 was pretty bad, but the tap remained on. In retrospect, a ‘Christian honeymoon’ period of 13 years is pretty remarkable, but I didn’t know that at the time. Converted into charismatic Christianity in my mid-teens, I had enjoyed a loving and life-giving experiential relationship with God.

And then I didn’t.

In the moment when my nightmares came true, the feeling of God’s loving presence disappeared. For several years I scoured my tradition for answers. I remember in 1998 my wife and I moved to a new home, and near our house was a poster asking a very pertinent question: ‘If God feels far away, who’s moved?’ I felt the salt being rubbed into my wound, as I had spent the last two years repenting of every sin I could think of and having all kinds of prophetic words spoken over me.

Apologies for the graphic detail, but the dark cloud began to let in the light one day while I was on the toilet. I am a bit of a book lover, and at some point I had bought a second hand copy of a book called ‘The Dark Night of the Soul’ by St John of the Cross. ‘20p’ was written in pencil in the inner lining. I’d never read it, and I think I’d probably bought it to look cool on my bookshelf. John was a 16th century Carmelite friar who wrote a much more substantial book on spirituality, of which ‘The Dark Night of the Soul’ is one chapter. You’ve probably heard of it.

John suggests that if you are experiencing God’s absence but not in active rebellion against God or doubting God’s love, you are probably experiencing a DNotS. He thinks this is the equivalent of God removing the stabilisers/training wheels from our bikes. It’s not a permanent condition but a necessary part of growing up that we learn to trust God without the good feelings that can come with spirituality.

I sat on the loo for a long time while I read most of this short book in one, er, sitting. I’m still not sure I agree with John that the Father absents himself to teach us a lesson, but a new idea had entered my mind: what if this isn’t my fault? I began to realise that my very real spiritual and emotional depression was caused not by my sense of God’s absence, but by what I thought this absence meant: I was a bad person who had displeased God. Somewhere along the way I had picked up the idea that God’s presence and activity in my life was a reward for good behaviour, and it’s inverse was punishment for sin or ‘lack of faith’. Just stepping out of this worldview with John allowed me to see how much judgement I was pouring onto myself.

Around that time I was reminded of another book on my shelf, one that I had at least tried to read (but never finished). M Scott Peck was a psychiatrist who was also a Christian, although his book ‘The Road Less Travelled’ is meant to be read by everyone. Early on in the book, he says this:

‘Life is difficult. This is a great truth, one of the greatest truths. It is a great truth because once we truly see this truth, we transcend it. Once we truly know that life is difficult-once we truly understand and accept it-then life is no longer difficult. Because once it is accepted, the fact that life is difficult no longer matters.’

These are just five sentences, but I have found it important to go back and meditate on them. One of the things that we absorb from our 21st century western culture is the idea that our purpose in life is to be happy and successful. If we are not happy and successful then something is wrong. I really feel Chris Martin’s pain when he sings, ‘Nobody said it was easy/No one ever said it would be this hard’ (from ‘The Scientist’ by Coldplay), but before Chris was even born Dr Peck was indeed saying it.

Why is this important? Because when terrible things happen they are not aberrations: they are normal. This is life, and as much as possible, I need to live it, rather than expend what life I have wondering why it’s happening to me the way it is. I’m not saying that everything in life happens by chance, just that not everything bad happens because you’ve done something wrong or someone is out to get you. Life is difficult. If we refuse to accept this we will be weighed down our whole lives.

I’m sure everyone reading this blog has a copy of Principia Mathematica by Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell. You probably leaf through its three volumes most days, I imagine. It is considered to be one of the philosophical foundations of modern mathematics and its second edition is nearly 100 years old. Of the two, Russell is the more famous, since in the interwar period he was a world-leading voice for both materialism (the belief that matter is all there is) and atheism. Whitehead is more interesting character now, and his own view, called ‘Process Philosophy’, is now coming into its own.

Unlike Russell, Whitehead believed in God, so in many of his books he called his beliefs Process Theology. If you know about Whitehead, please look away, as explaining him in one paragraph is impossible. The important thing for me, as someone coming to terms with the messiness of life, is that Whitehead believed that God is experiencing all of life with us. He believed that God had two ‘poles’, one of which is outside space and time, and one which is very much part of it. As the universe grows and evolves, God experiences all these changes with us, and in some ways is changed along with us. This is a much better description of the God of the Bible, who is very much inside time, sometimes changing his mind when he gets new information, and reacting passionately to what we do and what happens to us.

I find this image of God to be much more Christlike than the God of the Greek philosophers, who is cold and distant and completely unaffected by what happens to us. But there are some more challenging ideas too: because God has entered the universe in order to have dynamic relationships with us, God doesn’t control everything, nor does God know everything that will happen, because we have free will and God is travelling through time with us.

I know that for some reading this it will be hard to give up the idea of a God who is outside time and completely in control. All I can say is that Whitehead’s view (although dense and quirky) feels more like the God I know through Jesus and who I experience comforting me in my struggles.

Ah yes. Jesus. He’s the rabbi I’m referring to in the title. John tells a funny little story about Jesus that has the ring of truth about it. His disciples ask the standard theological question when confronted with suffering, either our own or that of others: ‘Why?’ They are trapped in the worldview I outlined at the start of this article: ‘Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?’ (John 9:2 NRSV) Someone must have done something wrong for this to have happened, and it seems a bit mean for this man to be punished for life for a sin committed in the womb, so was it his parents?

The first thing Jesus does is dismiss this question out of hand: this bad thing did not happen because anyone did something bad. We need to hear Jesus say this over and over again. Then he says something shocking: ‘He was born blind so that God’s works might be revealed in him.’ In the rest of the chapter we see how this works out: the pharisees are repeatedly befuddled by this miracle and choose not to believe in it. At the end of the chapter, Jesus contrasts their spiritual blindness with the man’s healing. God’s works have indeed been revealed, although not to everyone.

But how are we to take this? Is everyone born with an illness or disability intentionally made that way by God so that they can be healed later for evangelistic purposes? It seems unwise to universalise this statement into a theology about every instance of birth blindness. In my mind’s eye, I hear Jesus saying, ‘Why are you looking for a reason for this man’s disability? But God can give purpose even to this, by revealing himself through the man’s healing.’ This chimes to me with Paul’s wrestling with his own chronic illness:

Three times I appealed to the Lord about this, that it would leave me, but he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness.’ So, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may dwell in me. Therefore I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities for the sake of Christ; for whenever I am weak, then I am strong.

(2 Corinthians 8-10)

Why do I say Paul had a chronic illness? Isn’t that a very modern term? It’s true that some have suggested that Paul might have struggled with degenerating sight or even forbidden sexual desire, but the reason I’m using that catch-all term is because I have chronic illness. I’ve been unable to work for over two years and I’ve been told by doctors that recovery is very unlikely.

One of the ways my illness expresses itself is through the condition known as fibromyalgia, which is just a doctor’s way of saying painful muscles. All day, every day, I feel as though I have flu and ran a marathon yesterday. Or ran a marathon with flu. You get the idea. It’s not much fun, but love and friendship and an occasional board game can keep my mind off things for a while.

I have never once asked God, ‘Why?’ I have never once asked God, ‘Where are you?’ I hope you can see from the above why these questions don’t mean that much to me anymore. I have certainly had to process a lot about my identity, since I was a very activist Church Minister before I got ill. Now, my main project is me, and there is plenty to be getting on with. I have to sleep a lot, and my productivity is not what it once was: Jon first asked me to write this article many months ago!

My life is Christlike in ways that I had never expected: ‘We accounted him stricken, struck down by God, and afflicted.’ (Isaiah 53:4) The challenge for me is to respond with Jesus, ‘That’s not it all, look what God can do with this broken person’ and with Paul, ‘If I am not to be healed, then let God be revealed in my weakness.’

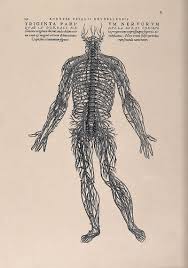

Image Credit: Commons Deed via RawPixel